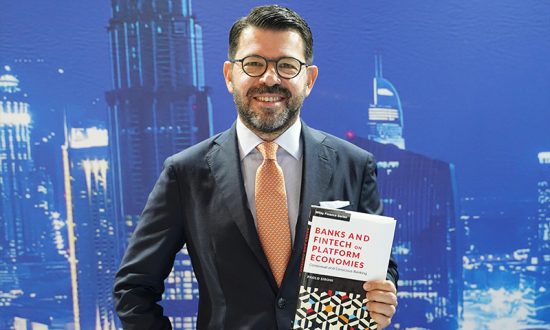

Paolo Sironi is the global research leader in banking and financial markets at IBM, the Institute for Business Value. He is a former start-up entrepreneur and quantitative risk manager in investment banking. Paolo is the author of literature about finance, banking, and digital innovation. His latest bestseller “Banks and Fintech on Platform Economies” explores how platform theory, born outside of financial services, will make its way inside banking and financial markets to radically transform the way firms do business. For more information, thePSironi.com.

Today it is clear: digital platforms are “eating the world”, transforming the experiences of consumption of goods and services, and the ways of socializing. Did you take an Uber to go to work? You booked it on a digital platform. During a coffee break, did you read about my latest literature on LinkedIn? You found it on a social media platform. Was it delivered to your doorsteps by Amazon Prime in less than 24 hours? You ordered it on an e-commerce platform.

The advent of “platform economies” is a tsunami for the traditional business culture. Sustainable business performance is no longer based on linear relationships between product manufacturers, distribution channels, and consumers with the logic of incremental production of costs and value. Instead, the main economic levers lie in the ability of new business models to engage users continuously, and usher in a new era of “hyper-personalisation” and “hyper-contextualisation”.

Client centricity is about motivations, not products

This corresponds to a business shift from “product centricity” to “client centricity”. And clients’ motivation is core to a successful digital business because digital platforms require users to interact and self-direct on virtual venues, apps, and websites. Platforms have to match the interest of individuals and entities which did not previously know each other; they have to consume products and services based on their capability to understand the value offered in the intermediation process. This is never easy, also on e-commerce platforms, and requires data and analytics to support client choices. It is even more complex in financial services, as the real product bought is financial uncertainty. If we order a Gucci bag on Amazon but the color doesn’t really fit, we can always return it and be refunded. Instead, if we invest in a risky financial product and we lose money after a few days, we cannot revert our choice. This is the reason why financial decisions are hard for many to make, and they largely depend on human relationships to be finalized.

Whatever the industry we are in, only a deeper understanding of ultimate human motivations to act and consume allows innovators to master digital engagement, in which human intervention is minimized, and launch positive network effects. In the rush to innovate, this foundational element of platform theory applied to financial services is often disregarded by start-up entrepreneurs. Instead, it plays a critical role, especially in banking and insurance given the nature of the intermediation. Most financial products are “sold” more than “bought”, as the industry is largely offer-driven. Instead, mobile technology is more a technology of the “demand”: we go on Amazon to buy a book on fintech, not generically to learn what is happening. How can financial services become digital, putting an “offer-driven” industry on a “demand-driven” technology?

It’s marketing stupid! Or maybe not.

In this regard, I want to share a personal experience. I was working in investment banking in the 1990s, supporting my brother part-time to launch an online marketplace called Intrade. We wanted to sell over the internet the best of Italian products and design: fashion, furniture, food, and travel. Buying design furniture on Amazon might be common practice today, but it did not seem so normal back in the 1990s. How to onboard distant producers instead of next-door businesses? How to simplify payments and make them trustworthy? How to ship goods safely and cheaply? How to onboard final consumers? All the key questions were on the table. Notwithstanding entrepreneurial enthusiasm, the marketplace never took off. Mistakes were clearly made, and too many faulty assumptions were taken about consumer habits. However, there is a major lesson learned that is worth sharing: we did not crack the code to build user trust and motivate consumers to interact. Instead, this is what Jeff Bezos understood, and explained some years later in a press interview. Jeff Bezos came to recognise that trust was the root of the problem, hence Amazon found the solution. He understood what kept many internet users inactive and motivated them to trust e-commerce.

Amazon was born in Seattle as a niche marketplace to sell academic books, soon evolving into a fully-fledged online store. Already selling to computer geeks is not the same as selling novels to the general public. Professional communities tend to know exactly what they want to read. Instead, the general public might need more support to choose a book. The difference is about buyers’ confidence with regard to the perceived value of what they purchase, trusting that the book’s content would match their reading expectations. Jeff Bezos once recalled how often publishers used to complain that Amazon users could openly share negative reviews on the web- pages. They insisted that only positive reviews had to be published. “It’s marketing, stupid!”. Or not? Publishers misunderstood the nature of Amazon, which was not a distribution channel of books on the internet.

Are fintech and neo-banks distribution channels of financial products on digital?

Similarly, we can ask ourselves if fintech start-ups and neo-banks are distribution channels of financial products on digital. Rather, Amazon’s role was, first and foremost, to provide advice to its users about the best book to buy. Advice was needed because readers were not used to buying books online, could not touch the product and read sample pages, could not speak to a bookstore manager, and get guidance. Publishing positive and negative reviews was the necessary mechanism to build trust. Bezos understood that motivating users to trust the value of their purchases was the first and foremost challenge for Amazon to turn visitors into consumers. If the motivational element was missing or not would be a make-or-break feature. If client motivations are not properly addressed, no marketing techniques will be truly effective. Meaning, clients will onboard but will not generate transactions. This is particularly true in financial services, as a regulated industry. Therefore, posting negative reviews was the transparency-based mechanism to generate trust in the Amazon platform, turning users from window shoppers to active contributors of value-based interactions. Only after user motivation was resolved, analytics could be used to reinforced and expand the user experience. Clearly, reviews must not be fake and kept free from potential abuse.

Transparency is a competitive advantage

Financial market transparency is the core governance principle of financial services platforms striving for higher business value. It generates trust to reveal value for clients. Fintech and digital banks need to understand this foundational element, linking platform theory and financial services practice. They will learn how to engineer the shift of core monetization elements from product / transaction fees to fees for accessing the platform, centred on advice and conscious consumption. When it comes to banking, data-enabling clients transparently to self-direct consciously precedes data-driven banking techniques – which also matter – to build successful digital offers.

Disclaimer: This is an excerpt taken from Paolo Sironi’s Amazon bestseller “Banks and Fintech on Platform Economies: Contextual and Conscious Banking”.

Book link: relinks.me/1119756979